Dumb like a painter

I'm here to make and consume art that's for everybody (and write a Substack for a niche bunch of nerds)

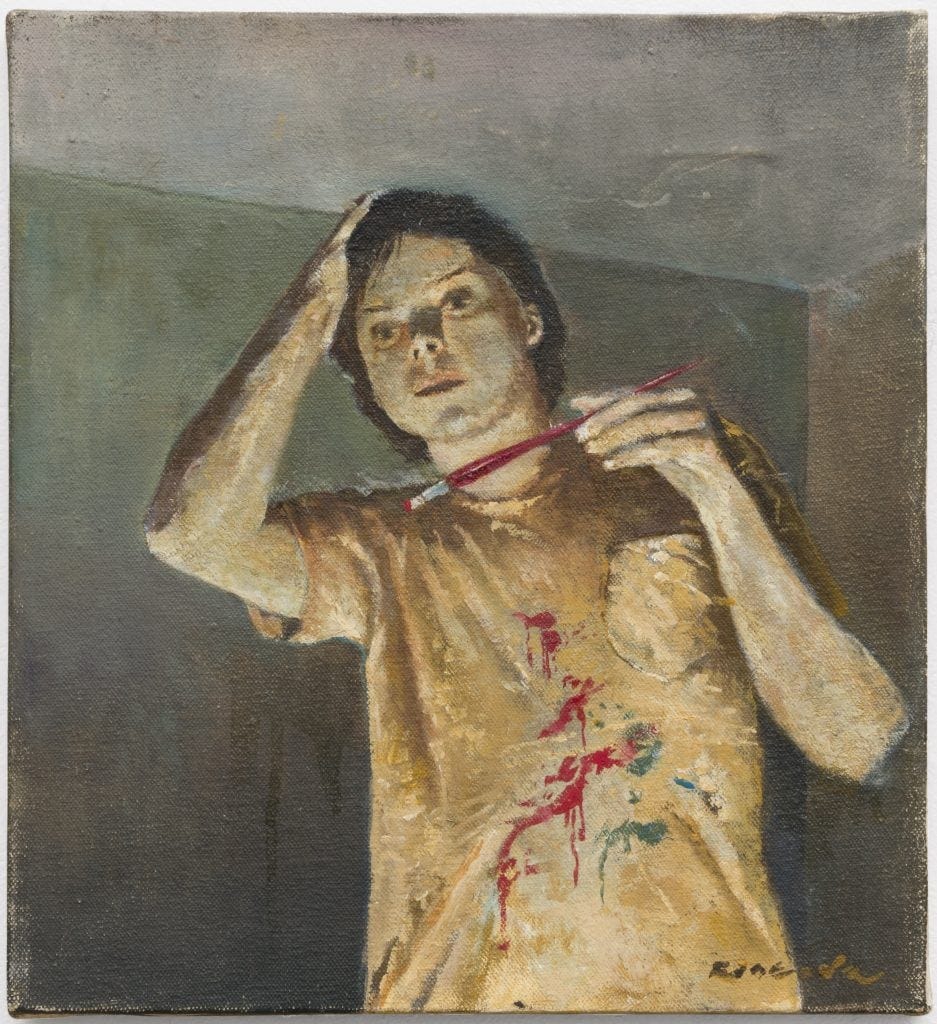

‘Dumb like a painter’ is an expression I first heard while in undergrad at the San Francisco Art Institute. It was coined by the Abstract Expressionist painter Willem de Kooning, and is taught to young painting students who might be thinking too hard about how to make something good or seem important.

What it speaks to - in my humble interpretation- is that painting, unlike language, can get to something beyond the crispness of word-articulated thoughts. It can reach into your energy field with color and form. It can express the ineffable.

For me, painting was there when I went through periods of adrenal burn-out and couldn’t form full thoughts without having OCD intrusions. At the time my nervous system was so out of wack, I could barely experience life without having some form of fight or flight response to the sensory overload of pretty much anything happening other than sitting in a quiet room. When my mind wasn’t a safe place, painting was there.

And so while good painters aren’t dumb, the best of them - again in my humble opinion - make their work from a place that goes beyond strategy and articulation to get at a resonance, a harmony, or a feeling. Sure there may be an architecture of history or concept that the work is hung on, but a good painting will resonate with folks of all walks of life, often in their bodies more than their minds.

This is something I’m not sure I have always believed, but have come to feel more strongly about, looking at life from both sides now. I have done a 180 in terms of what motivates me on a daily basis, from reaching for art world stardom in my 20s to just getting through the day feeling like I am being true to myself, and hopefully making something of value to me and people I respect.

As a result of this internal shift, but also my upbringing which taught me to love kitsch, Bob Ross, corn dogs, and mid-western culture (dontcha know), I have become, more than ever, a populist.

One of the conversations we have been having at the artist’s studio where I work is debating where we (two Cal Arts-educated artists and myself) stand on the lifetime oeuvre of Thomas Kinkade. By that I mean the whole of his work, since taking in a singular painting of his and judging him by it is, pun intended, only part of the picture.

Even so, I would still appreciate his delicious use of light, and syrupy subject matter for the kitsch and problematic nostalgia that it is. And I would wonder about his true intentions. Was he a conceptual art genius deep undercover? A relatively benign Christian cult leader? Or was he a closeted-about-something artist with decent enough intentions who got trapped by his own success? I wish it were the first, but my money is on the third after seeing the trailer for the newish movie, Art For Everybody, which puts the kink in Kinkaid. After his death, the movie tells us, his family discovered 1000s of dark, unreleased paintings of his that are a far cry from his snowy cabin works - and the mystery unfurls from there.

But despite all the problems with Kinkade’s work and pyramid scheme business model, I do believe somewhere in him there was a desire to bring art to the masses. He talks about making art accessible to people who otherwise wouldn’t want it, or who thought fine art would be beyond their means. I mean, say what you will, but the proof is in the pudding that his work is popular with his massive audience of repeat customers.

This idea brings me to a newly released article in Art Review, “Don’t Listen to the Art Gurus,” that prompted me to write this essay. “DLTTAG,” which I disagree with, gets to the heart of some of these same studio conversations we have been having about the dumbing down of art and culture to appeal to a wider audience, and of course, their purse strings.

The author, Rosanna McLaughlin, writes that thanks to music industry celebrities like Brian Eno and Rick Rubin, there has been “an extraordinary dumbing down of culture… smuggled in via the promise of inclusivity and anti-elitism.”

Ok, my first issue with this article is the examples McGlaughlin chose. When I think of celebrities who would dumb down the reader through their writing, I think of reality stars like the Kardashians or pop-star icons like Justin Bieber (no offense guys, it’s just your brand). I do not however think about previously obscure-to-me music producers. I grew up on Rick Rubin’s music, and only just learned his name when I bought his book, The Creative Act: A Way of Being.

The word celebrity also suggests that the main quality these people have going for them is that they are well-known, but somehow their talent as some of the most successful music producers of all time doesn’t warrant them sharing their creative wisdom? Hmmm. I’m already confused.

But moving forward as if there’s a solid argument to be made, perhaps with other examples, I would say my other problem with it is that I loved Rick Rubin’s book. And have not read Brian Eno’s. I, an art school grad and someone who writes occasionally in a way that requires me to cite sources and research other texts, really enjoyed the loose format and poetic language. I treat it like a tarot deck that I open to a random page and then see what little kernel of wisdom might be helpful as I go through the day.

When I was in LA, depressed and invisible even to myself, I wondered how I should keep making art when no one cared. Finding a book that offered me a yes was a little shot of inspiration that helped me keep going in that moment.

Not only that, but books like The Creative Act are in dialogue with more traditional art texts like Ways of Seeing that McLaughlin cites in her article as a better, smarter version of art guru texts of the past. The issue I am seeing is we don’t need another Ways of Seeing because it has already been written. We need something that reflects the moment, and judging by its sales record of over 750k books, The Creative Act is currently what the people want, and maybe what they need.

If the socio-political context of the time helps to determine the cultural forms that will resonate most with audiences, it’s inevitable that certain styles or material approaches will come up over and over again in a sort of zeitgeist-y way. Ideas are channeled through the creators of a time as a way to get to something that is on the mind of the collective consciousness. I believe art that really resonates with a lot of people is made by artists for a greater purpose, whether we get the reason at the time or not at the time. Like who knew one of the side effects of the Beatles is they would make the, at the time disrespected, Northern English accent cool, thus reducing cultural classism in England?

But to come back to painting, we have had plenty of movements that seemed to be dumbing down craft, from the Impressionists to the Fauvists to the Abstract Expressionists. Matisse used to talk about the French Academy genre paintings and how all the work was Bouguereau’d, some by Bouguereau himself, to appeal to a certain class of educated audience with its brushless, photorealistic painting style and historical-but-make-it-sexy, subject matter.

Matisse’s work, along with the other major modern painterly movements were focused on deconstructing and sometimes “deskilling” what came before. Not because of a lack of talent or to make their audiences stupider, but because they wanted to say something that spoke to the moment, and that was the way it needed to be said.

And yes, at some point these movements overstayed their welcome and went from avant-garde to mainstream to passé and then back again to the canon eventually. In publishing there are similar movements, I’m sure, and like a pendulum, they will undoubtedly swing forever back and forth and sideways, pissing people off in the process.

But just because culture skews towards accessibility right now, and “the new wave of art gurus” are focusing on the metaphysical and therapeutic aspects of art, does it mean they are pandering to our basest interests as McLaughlin suggests? Are they really assuming “precious little of their readers’ cognitive capacity,” and ignor[ing] centuries of thought”? Or are they responding to a need? Even James Joyce, king of the opaque novel, wrote to his daughter at the end of his life that maybe he questioned the value of writing such inaccessible texts.

Footnote: this is something my English-major friend told me and I am scouring the internet to find the original source. Currently, all Joyce’s letters to his daughter are available as photocopies of the handwritten document, meaning they are in Italian in addition to the handwriting being as illegible as Ulysses. ( Zing! I love a good James Joyce joke.) If you know where I can find this reference please DM me and I will add it in.

As we are fully enmeshed in late-stage capitalism, barely holding on by a Niro-embroidered thread, we have not only seen it all, but are constantly bombarded by new content. Maybe the prevalence of self-help-y, creativity manuals by trusted names is what the people need right now because we are overwhelmed and looking for a way to tend to our squishy parts, not our logical brains. Maybe we need to enjoy reading about art in easy-to-understand, playful, language that makes us want to take out our watercolors and make a Sunday painting. Is that so wrong?

I don’t want literature to homogenize, and I don’t, by any means, think that we should only be producing structure-mush books like The Creative Act, which again I loved. But I do think that there’s a reason people are being called to both consume and create works like that over the past few years.

That’s all I got for now. Would love to hear your thoughts.

There’s something about creation that brings something nurturing back to your life, where it reminds you that we are put on earth to do more than just survive. We have lots of other complex thoughts, and I don’t know, it’s something that soothes me a lot. In a world where we have so little control, I feel like being able to write a song is the one thing that I still have control over. Minimal, but still.

– Brontez Purnell, via The Creative Independent.